Sarasin - Growth without inflation? Immigration can help

Rich economies are benefiting from higher growth with modest inflation thanks to a surge in immigration. That could boost companies’ earnings potential – and investment returns.

The economics of immigration is complex, but one thing is clear: the recent surge in new arrivals to developed economies has been good for growth, without adding much to inflation. With

immigration into the US, Canada, the UK, Spain, Germany and Australia at extremely high levels, the benefits for investors are being felt widely.

Some of the recent surge reflects a catch-up in well-established migration patterns that were interrupted by the pandemic. Success attracts success: booming economies attract people. In addition, deteriorating geopolitics and outright conflict have created a wave of people seeking a better life elsewhere (or at least safety), with Europe and North America receiving millions of Ukrainian refugees. Immigration is showing up in much faster population growth.

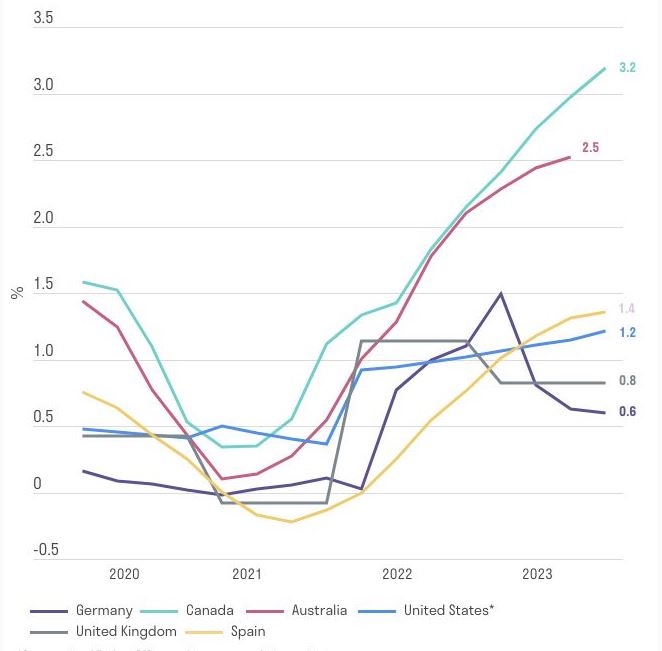

Chart 1 Population growth is surging

*Congressional Budget Office working-age population estimate

Source: Macrobond, 04.04.24

Immigrants mostly comprise workers, international students and humanitarian visa holders. Tourists are not counted as immigrants or in population statistics. However, drawing a bead on actual immigration levels can be difficult.

US census population figures underestimate immigration due to difficulties in measuring illegal immigration. The Congressional Budget Office recently estimated net migration in 2023 and 2024 to be around 3.3 million per year (close to 10,000 per day), figures that suggest that migration is almost certainly having a major impact on production and consumption in the US economy. [1]

Demand holds strong despite higher rates

Major economies defied near-unanimous predictions of recession in 2023, partly because simply adding more people meant that each person would need to cut spending by more for gross domestic product (GDP) to fall in aggregate. At the time, this went largely unnoticed: population growth is usually a slow-moving affair, so it often doesn’t feature prominently in forecasts of the business cycle.

Extra people add to demand by consuming goods and services. This typically boosts the consumption component of GDP, the exception being international students, whose spending is captured in exports. The investment component of GDP may also have to increase for the economy to supply this additional consumption and exports over the longer term.

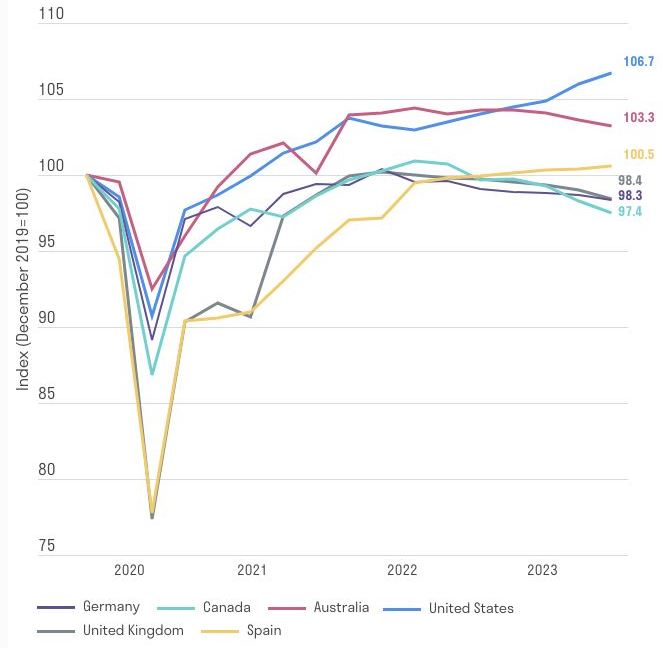

Under the surface, GDP per person has actually been falling in developed high-immigration economies. Although the US appears to be an exception, it is less so once you adjust for under-reporting of net migration. The decline in per-person GDP gives us some confidence that higher interest rates from early 2022 (alongside higher energy prices) have indeed helped to slow previously rapid growth – a fact which is less obvious in the aggregate GDP data, particularly in the US.

But we have to be careful of compositional effects: falling per-person GDP may also occur if incoming migrants spend or earn less than the existing population. That means we need to keep an eye on the labour market as well.

Chart 2 Real GDP per person

Economics are slowing as hoped

Source: Macrobond, 03.04.24

People are both consumers and producers

Most people work, which adds to labour supply in the economy, and everyone is a consumer at some level. Some migrants, such as international students, may consume more than they produce, partly because of restricted working rights. Other migrants are likely to be net savers. The same person may be either at different points in time. When I first moved to the UK, I was temporarily a net consumer, living off my personal savings until I found a job.

With a lot more people looking for work, the US economy was able to add a massive 3 million extra jobs in 2023 and still see the unemployment rate trend up marginally. Slowing wage growth also suggests that labour supply is increasing faster than demand at the moment, even if some of that extra labour supply is not being captured in official statistics.

In Canada, Australia and Germany, where GDP growth has been slower, the number of jobs created has not kept pace with the number of people looking for work. This has seen unemployment rates in these economies tick up from their post-pandemic lows.

Oddly, despite the UK also experiencing the same combination of weak GDP and strong population growth as these other economies, the official unemployment rate from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) has been falling, calling into question the reliability their labour market data.

Disinflationary boom

When people consume and produce in similar amounts, immigration can boost GDP growth without adding much to inflation. So the US could experience stronger-than-usual GDP growth while its inflation falls towards the Federal Reserve’s (Fed’s) target of 2%.

In other economies, however, a mix weak growth and rising unemployment is likely to cause headline inflation to return to target earlier than in the US, despite a much higher starting point at the start of 2023.

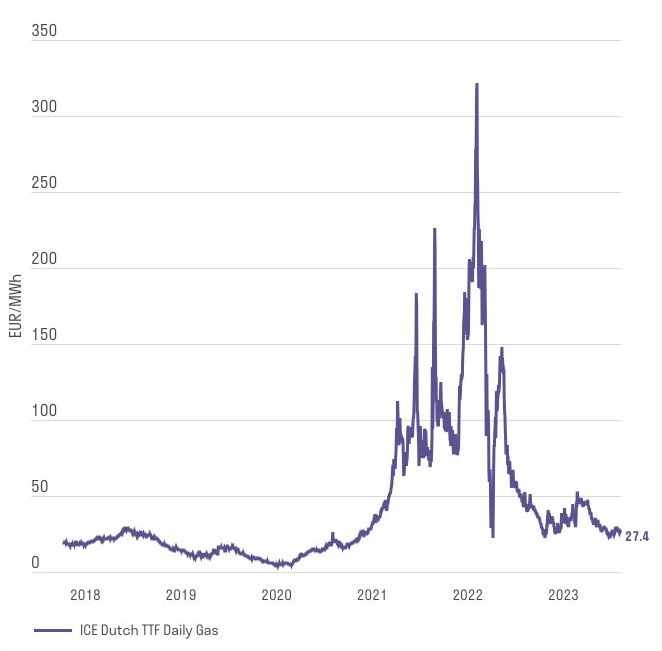

Indeed, recent monthly inflation data has been lower outside of the US. Price increases for goods have slowed rapidly compared to services as energy prices and supply chain pressures have normalised despite ongoing geopolitical issues.

European wholesale energy prices are plummeting as supply and export capacity of liquified natural gas continues to grow. The significant historical price difference between US and European gas looks likely to be arbitraged away in coming years as gas markets become increasingly globalised. This is positive news for energy importers like the UK, Europe and Japan, and could support their currencies.

Chart 3 European wholesale energy prices are plummeting

Source: Macrobond, 10.04.24

Cheaper Chinese imports are also helping bring inflation back to target (but I doubt they will receive a thank-you letter). China is trying to offset a housing market downturn by exporting manufactured goods and building yet more infrastructure.

Housing markets feel the strain

The housing market is one part of the economy that can’t expand supply rapidly to meet extra demand. Even in areas where building is permitted, housing takes time to build. The influx of people, together with a preference for more living space prompted by the experience of pandemic lockdowns, has seen rents skyrocket.

High rents have meant property price falls have been modest relative to the increase in interest rates. In the US, rents account for around one-third of the consumer prices index (CPI) and are a major reason behind persistent inflation. In the UK, the ONS has recently revised its approach to calculating rent inflation. Its new methodology reveals that over the past year UK rents have been growing at close to 10% rather than 7%, as was previously thought [2].

Chart 4 Housing rental CPI inflation influx of people sees rents skyrocket

Influx of people sees rents skyrocket

Source: Macrobond, 03.04.24

The Fed still has scope to cut interest rates

Disinflationary booms are positive for risk assets because stronger GDP growth means better earnings potential. At the same time, the Fed should still be able to start cutting interest rates, even with GDP growth modestly above 2%, provided it still thinks inflation is coming down.

However, an economy with strong population growth can sustain higher interest rates over the medium term, and investors will need to take this into account – particularly when valuing fixed-income investments.

This reinforces our view from last quarter where we wrote that the long-run destination for the Fed Funds rate is more likely to be 3.5% [3] than the median estimate of around 2.5% [4] from the Fed itself. We are entering a new regime in which inflation, interest rates and asset price volatility will all be higher than during the 2008-to-Covid era.

[1] Sarasin research, January 2024

[2] US Federal Reserve, 'Summary of Economic Projections', March 2024

[3] Source: Office for National Statistics, Private rent and house prices UK, March 2024

[4] Congressional Budget Office, 'The Demographic Outlook: 2024 to 2054', January 2024

Important information

If you are a private investor, you should not act or rely on this document but should contact your professional adviser.

This document has been approved by Sarasin & Partners LLP of Juxon House, 100 St Paul’s Churchyard, London, EC4M 8BU, a limited liability partnership registered in England & Wales with registered number OC329859 which is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority with firm reference number 475111.

It has been prepared solely for information purposes and is not a solicitation, or an offer to buy or sell any security. The information on which the document is based has been obtained from sources that we believe to be reliable, and in good faith, but we have not independently verified such information and no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy. All expressions of opinion are subject to change without notice.

The value of investments and any income derived from them can fall as well as rise and investors may not get back the amount originally invested. If investing in foreign currencies, the return in the investor’s reference currency may increase or decrease as a result of currency fluctuations. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results and may not be repeated. Forecasts are not a reliable indicator of future performance.